BARRIERS TO TRANSPARENCY: Business and competition

The first and most obvious obstacle is business. Sharing sensitive financial data makes us uncomfortable as it could negatively impact our bottom line. Will customers complain when they see the margin we earn for our labor? Will our competitors use that information to steal our precious coffees by offering producers slightly more than we pay?

These are valid concerns and highly probable scenarios. The only defense against them is trust, the kind of comes from long term and mutually beneficial relationships. Customers must trust the work we do and the value we add. Producers must trust us to come back to buy the coffee year after year, which would make it less attractive to sell at a higher price to a one-off buyer. We must also welcome the competition and pay higher prices, trusting our customers, and their customers, will be willing to pay extra too.

BARRIERS TO TRANSPARENCY: Which number do we share?

Percentage above…

You may have seen claims like “we pay an average of 20% above,” “twice the market price,” or some other multiplication of the C-Price. This is an easy way to contextualize the high prices paid for specialty coffee, and we admit to doing something similar ourselves. But it is a fundamentally flawed comparison because, as most in the specialty industry would agree, the commodities market is a flawed system.

FOB

The most common number shared by specialty coffee companies who practice transparency is the FOB. This stands for Free On Board and it represents the price paid by the importer to get the coffee out of the country. Consider it the moment the crane carries the container of coffee from the dock to the ship.

The reason the FOB is the most commonly shared number is because it is the number those of us working in the markets know and can verify. As importers, this is the price CCS pays for the coffee, and we can prove it with our purchase contracts.

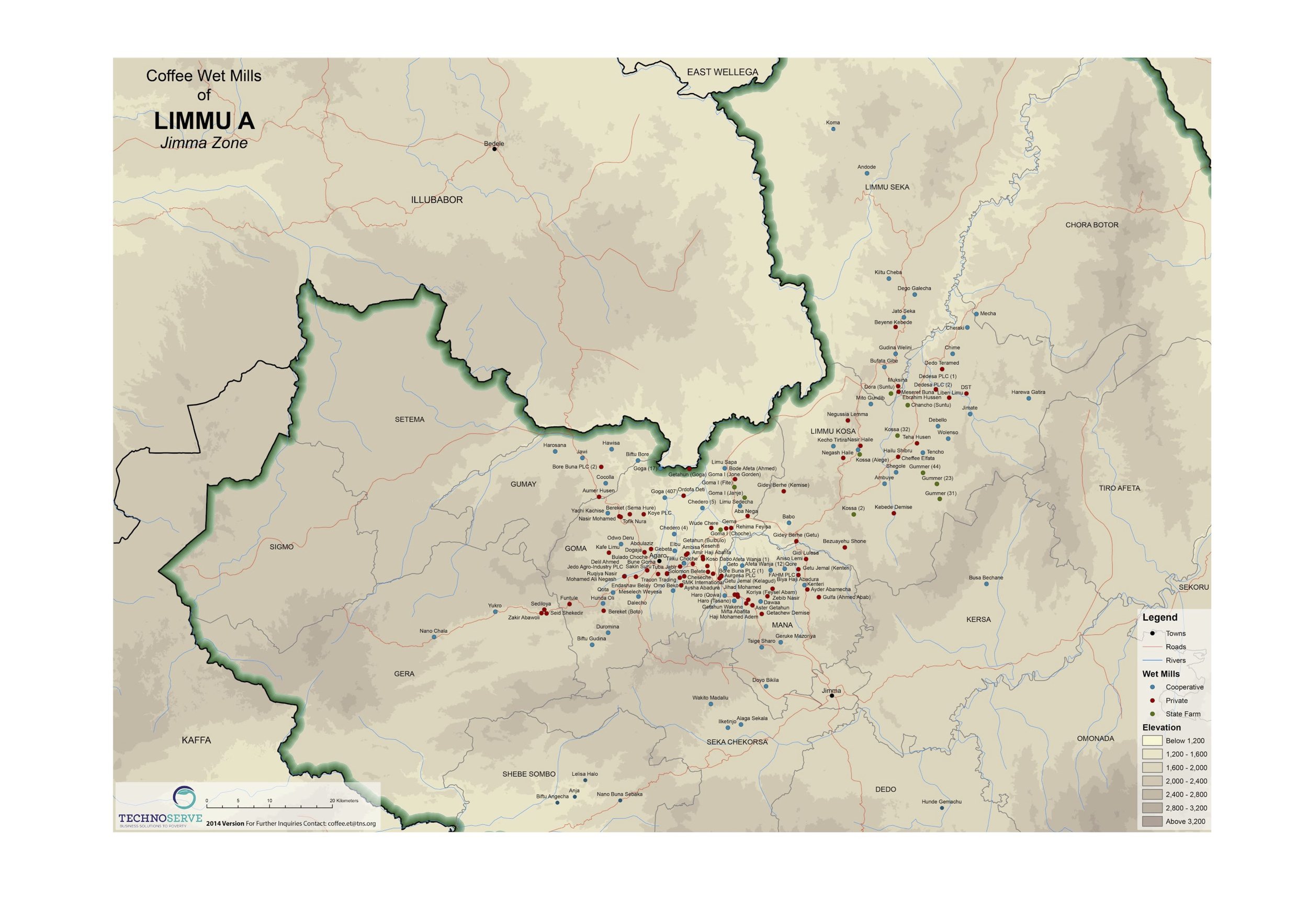

The problem with the FOB is that it says little about how much the producer was paid. Included in the FOB price are many additional costs, such as milling, storage and transportation. There may also be an exporter’s fee, which covers their work in sourcing the coffees, supporting and training the teams that cup these coffees, possibly paying agronomists who advise the producers. Often it includes origin country taxes and insurance.

Return to Origin (RTO)

Based on the FOB, several roasters have begun publishing percentage they call Return to Origin, or RTO. This is the FOB as a percentage of the final cost of roasted coffee. A 20% RTO means that 20% of the final price of that roasted coffee was paid to people in the country where that coffee was cultivated.

This is an interesting initiative, and hats off to the roasters who use it. However, the risk of publishing the RTO as a percentage is that a higher percentage looks better, it suggests more money in the pockets of people at origin, but that isn’t always true. It really depends on the final price of the roasted coffee; 10% of a high-priced coffee might mean more money than 20% of a cheaper coffee.

FOT

Free on Truck (FOT) is the amount paid when the coffee is transferred to a truck for transport, and it is hard to know if this was paid to a producer, or another actor along the supply chain. FOT might be paid to a farmer, but it is more likely it was paid to a washing station, dry mill or exporter who must then transport the coffee to port.

Farm Gate

A more accurate reflection of what a farmer earned is called the Farm Gate price. This is the price paid the moment the coffee was transferred from the hands of the producer. Once again we encounter problems with this figure.

Firstly, the Farm Gate price is almost never the price paid for green coffee, as producers usually deliver cherries or parchment. Calculating the price paid for green coffee based on the Farm Gate is complicated by a number of different factors, all of which impact the amount of green coffee derived from the delivery. Even when the producer is delivering dry parchment, coffee in its final state before milling, there is no easy equation to calculate the amount of green coffee purchased. This depends on the yield factor, which is the amount of green coffee produced after waste from parchment and any impurities like stones and sticks is discarded. As you can imagine, the yield factor can vary from lot to lot.

Each step in processing coffees carries with it loss and risk. The loss is in the form of cascara, pulp, humidity and parchment. The risk is that something goes wrong during processing that could impact the quality of the coffee, lowering its value. The more loss and risk a producer carries, the more they are paid for the product they deliver. This makes it almost impossible to compare a Farm Gate price paid to a producer in Colombia, who processed their own coffee and sold it as dry parchment, to a Farm Gate price paid to a producer in Ethiopia, who sold fresh cherries to a washing station.

Similarly, it is difficult to compare these numbers without understanding the cost of production in each origin. And imagine the producer delivered their coffee over a series of weeks, with differing yield factors, price fluctuations and changing currency valuations.

The calculations get complicated.

LACK OF CONTEXT

The biggest obstacle to transparency is context. A single number can not communicate the long and complicated supply chain of coffee, and the costs associated with delivering it. Nor can it account for variations in cost of production, cost of living, currency fluctuations or volumes produced.

There are efforts to improve this. Colombian coffee exporters, Azahar, presented data to those gathered in Hamburg from their own study into providing their producers with a living wage. Working with 100 farms in three departments in Colombia, they determined three price points for a carga (125kg) of parchment, which is how most Colombian producers sell their coffee. The three price points indicated the price Azahar needed to pay in order to:

- Meet the poverty line

- Meet the minimum wage in Colombia

- Meet the minimum wage, plus enough extra to reinvest in developing the farm.

The fourth column, which contained only question marks, asked “How can we do better?”

This data goes a long way to contextualize the Farm Gate price, and is a great potential model for other companies buying green coffee. However, for now, its scope is limited.

MARKETING TRANSPARENCY

“Transparency is not marketing,” Peter Dupont noted, “but we do need to market these numbers better.”

Our customers do not have time to investigate the supply chain of every product they buy, they need at-a-glance information in order to make their purchase decision. This is something Fair Trade understands well.

More importantly, consumers need to believe transparency matters.

No profit in transparency, yet

Operating transparently requires an enormous amount of work. It means asking everyone in the supply chain to keep and share detailed financial documents, which need to be understood, analyzed, distilled, then formatted, packaged and communicated to customers. It means research into local economies to provide context for these numbers.

It is difficult for small specialty coffee companies to justify the additional expense unless the customer is willing to pay for it.

This is the crucial link in the transparency chain. We must convince customers to demand transparency, even if they don’t have the time to analyze and understand the data we provide them. “Ultimately, no one will choose to pay producers more for coffee,” Peter W. Roberts said, “the market has to force it.”

For transparency to make business sense, we need to convince consumers to ask:

1. "How much was the farmer paid?"

and

2. "Is that enough for them to live?"

If enough consumers ask, everyone in the supply chain will make it a priority to find the answers.

Share what you have

The overwhelming agreement in the few days spent in Hamburg was that transparency can’t wait until we have perfect data.

“We have to start somewhere,” Peter Dupont added, “then push the conversation forward,” even if that means we start with the FOB.

Professor Peter W. Roberts is working on research to strengthen transparency in specialty coffee, but even he noted “we can’t ask you to share data you don’t have.”

This is the reason the research to create a Data Backed Transaction Guide for the Specialty Coffee Market will begin with the FOB. It is an imperfect number, but it is the one we all have and can verify. The hope is that the breadth of the data in this pilot study will be robust enough to encourage further research into producing better numbers.

TRANSPARENCY AT CCS

Transparency is one of our core values, and yet we have struggled, as have so many companies in specialty coffee, with all of the above issues. In the past we have shared the FOB of the coffees we buy with our customers, but we have not published them for fear of misrepresenting what the farmer is earning for that coffee.

We have been pushing for better data, from our producers and from our partners. We are trying to contextualize the prices paid for specialty coffee with the cost of producing such high quality. We have an initiative to source better data and create a methodology for people at origin to do this on a regular basis. Plus, we will be data donors for the Data Backed Transaction Guide mentioned above.

And, from today, in the spirit of the Hamburg colloquium, we will start with what we have. Below you will find the FOB of all coffees we have purchased so far in 2018. You can also find them on the origins pages on our website. We will do this for all coffees we purchase from now on.

FOB of CCS Selection, 2018

Kenya

Ethiopia

Colombia

Guatemala

CONTEXT

The FOB represents the price we pay our export partners at origin. To calculate the cost we charge to roasters, we add the following:

- Financing and logistics, on average USD $0.3/lb

(USD $0.4/lb for inland coffees such as Burundi).

We work with financing partners as we are an independent sourcing company without the capital to finance coffee. Logistics covers shipping, insurance and other costs to transport coffee from ports at origin to our warehouses located in Oslo, Hamburg, New Jersey and Oakland. This price is only for full containers. When we ship smaller quantities of coffee, like from Panama for example, financing and logistics costs are much higher. - Our markup to cover our costs.

The markup varies, depending on the FOB, volumes purchased, and the need to remain competitive in the market. For example, we take a lower margin on our most expensive coffees. On average, in 2018, our markup is 20%.

So the equation for all origins, except Burundi, looks something like this:

Price to roasters per pound = (FOB + US$0.3) x 1.2

Price to roasters per kilo = (FOB + US$0.66) x 1.2

The equation for Burundi looks something like this:

Price to roasters per pound = (FOB + US$0.4) x 1.2

Price to roasters per kilo = (FOB + US$0.88) x 1.2

Please remember, these are averages.

Push the conversation forward

“It’s not necessary to go from zero to one hundred in the first try,” said Meredith Taylor, Sustainability Manager for at Counter Culture. Their first transparency report included data on twelve coffee contracts. Now they publish details on over 300.

Publishing the FOB of all coffees purchased in 2018 is, perhaps, starting at five. Meanwhile we, and many of our colleagues in the industry, are working towards delivering one hundred.

Do you want to be part of the conversation about transparency in coffee? Share your thoughts below, and join the Transparency in Coffee Facebook Group.