98% of the coffee exported out of Ethiopia goes through the Ethiopian Commodities Exchange (ECX), so to say it’s important is a massive understatement. But it’s also a struggle to understand, makes transparency seem as out of reach as world peace, and causes a lot of misrepresentation about what Ethiopian coffee is and how the export process works. In fact, it’s almost incomprehensible as to why the ECX is so, well, incomprehensible. Anyone who imports Ethiopian coffee can attest to the resulting challenges, frustrations, and constant changes they experience when buying from this coveted origin.

So two stakeholders in the Ethiopian coffee trade have sat down for a Q&A on what the ECX is, why it makes it difficult to buy directly from source, and how the process may improve in the future. Read on to to discover what this confusing system is all about.

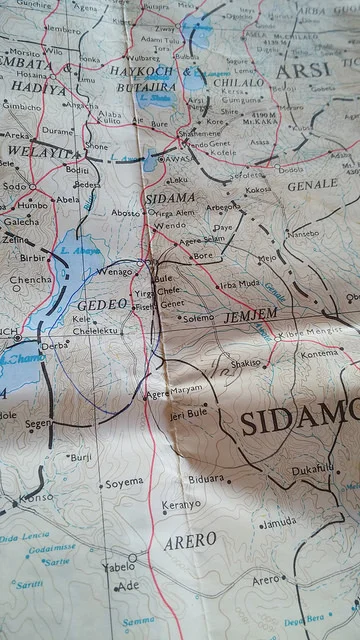

Coffee being processed in Gedeb, Ethiopia

The Q&A Participants

Heleanna Georgalis of Moplaco P.L.C. is an exporter of Ethiopian coffee. Her family has been working in the coffee trade in Ethiopia for three generations, and Moplaco was established by her father, Yanni, in 1971.

Melanie Leeson is a coffee buyer/importer for the Collaborative Coffee Source, whose founders have been establishing close partnerships with coffee producers and exporters since 2005 through their sister company, Kaffa Roastery, in Oslo, Norway. Since 2012, CCS has independently continued to strengthen these early partnerships and is continuously and thoughtfully adding new partnerships – producers, exporters, and roasters alike – to its supplier roster and customer base, which together span over five continents.

The ECX: A Q&A

Melanie Leeson: Heleanna, explain to me the different ways someone can buy coffee from Ethiopia. Is it possible to have direct trade Ethiopian coffee?

Heleanna Georgalis: Well, yes. You can buy in three ways:

1. Directly from Unions which form an umbrella on top of a number of cooperatives. Coffees bought this way can come in bulk (e.g. a Sidamo Gr-2) with no specificity behind it, or can come “directly” from the specific cooperatives you have chosen to buy from. This coffee can be fully traceable and recognisable.

2. Directly from a commercial farm that has a minimum of 35 hectares of land. These farms are also recognisable. They offer traceable coffee from their own land, along with coffee most likely collected from the farmers around them.

3. From an exporter who can ONLY buy their coffee from the auction. These coffees are not traceable and are only given general names from wider geographic areas. For example, a Sidamo A would include areas such as Bensa, Guji, and Harorensa.

Wild coffee trees in Kaffa forest

Melanie Leeson: Are there any downsides to buying from cooperatives via unions? Why doesn’t everyone who wants traceable coffee just buy from the unions?

Heleanna Georgalis: Although I’m not a buyer myself, I believe people may, in many cases, prefer to buy from an exporter, as they’ve already built a relationship of trust over time.

Buying from a cooperative and union, although they may offer the advantages of traceability and the access to see where and how the coffee has been produced, requires an enormous investment of time. This may form an impediment. And even once a relationship has been established with the cooperative, timely communication and reliability with the union-exporter may become hurdles. In addition, the farmers of the cooperative may not be the full beneficiaries of all these efforts.

However, this option still remains the best option for establishing a desired “direct trade”, as it allows you to deal as close to the origin as possible.

Processing Ethiopian Yirgacheffe

Melanie Leeson: Buyers see a lot of names of Ethiopian coffees in the market. Can you explain how all these names come about, given the fact that 98% of the total produced volume in Ethiopia is still bought from the ECX?

Heleanna Georgalis: There are about four different types of names an exporter, whether a union, farm, or private exporter, can use:

1. A general wider area, such as Sidamo.

2. A specific area, such as Guji, that can be accessed through the ECX because it’s graded as an 80+ coffee. In this case, “Guji coffee” becomes traceable to the wider Guji area. So this kind of traceability is possible for some localities traded through the ECX, but certainly not for all.

3. A specific location, such as Haricha. However, this is only possible if the exporter is a cooperative/union from the area that can directly trade the coffee as “Haricha”. Or if they’re a commercial farm that’s established in that area.

4. A brand that’s a registered name an exporter has given to their coffee.

Ethiopian Yirgacheffe

Melanie Leeson: Is it possible for an exporter to buy coffee from cooperatives and farms and then market these coffees using their names and locations?

Heleanna Georgalis: “Absolutely not” would be the definite and short answer to this. So when an exporter claims that a coffee comes from Haricha in Yirgachefe, you have to wonder how they know, given the lack of traceability inherent in the auction.

Equally, when an exporter says that their coffee comes directly from one particular washing station, you have to wonder – again – how they could possibly know this, since the coffees from a wider area are just blended together and then given a grade and a classification.

Where is your coffee really from?

Melanie Leeson: What was the rationale behind the creation of the ECX? Why the move to remove traceability in the coffee buying process?

Heleanna Georgalis: Let’s say “a lack of adequate information and understanding of the workings of coffee”.

ECX was formed out of the belief that Ethiopia would be able to eliminate or reduce poverty if commodities could have a platform to be traded on, rather than an informal system of supply mainly controlled by or benefiting the “middleman”.

However, coffee already had an established system and platform of trade that had existed since the 1970s. It was well designed to represent and trade coffee in a traceable and sustainable way. Like every system it had its drawbacks, but these were easy to correct.

The move to remove traceability emerged from a belief that if the exporter and the supplier of coffee could identify each other, then collusions could form that would distort the market and make it difficult and unfair for all the players to participate. So the most valuable information of the coffee was removed, but the collusions and special relationships that plagued the previous system have gone underground but have not been hindered.

Moplaco’s Yirgacheffe warehouse

Melanie Leeson: I read earlier this year that ECX was rolling out a geotagging system this season. Each bag now comes with a scannable code that will provide the buyer with its precise geographic information. Is this program operational? How is it working out?

Heleanna Georgalis: This system, although cumbersome to implement, and cumbersome for the logistics of any exporter’s warehouse, gave me the hope that the information we need would be restored to us. It would enable us to sell high quality coffee traceably.

At the moment, the system has not yet been fully established. Although efforts have been made to deliver tagged coffee bags to us, they cannot actually be read or traced. I sincerely hope that, as of next year, we will have a clearer view on how the system will actually operate.

Coffee picking in Gesha Village, Ethiopia

Melanie Leeson : What do you think about buyers’ demands for traceability?

Heleanna Georgalis: Reasonable, I would say. How can a product be “special” if it is bulked and blended with other products? How can you understand and appreciate the specificities of each coffee and location unless this information is available?

However, like many demands, this can also become a hurdle to both exporters and buyers in sourcing the best coffees they can. If Ethiopia exports 98% of all its coffees through the auction, it would be unreasonable to believe that this amount would not be sufficient to cover their need for a great coffee.

At the end of the day, traceability does not guarantee quality, although I would say that quality needs to be traceable up to a certain point. I do find some of the demands unreasonable, but then who am I to judge what people have to do to sell their coffee?

Cupping coffees picked and processed at Gesha Village, Ethiopia

Melanie Leeson: One final follow-up question on the geotagging system. As I understand it, the exporter buying a coffee from the auction cannot see or taste the coffee before it is purchased; it’s purchased simply based on the grade the ECX cuppers have given it.

Let’s say the geotagging system is perfectly operational – still, what’s the point of being able to trace the coffee if you have no way of buying it again? If you’re purchasing coffees from the auction with only the wide geographic region and grade as your basis for purchase, then what is traceability for? Other than simply to know where the coffee comes from.

Heleanna Georgalis: This is a very valid point for a person who needs consistency over time. In fact, it represents the exact point that our established new system needs to work on. However, an importer should also remember that, given the current state of infrastructure in Ethiopia, a good Guji Gr-1 wouldn’t taste fundamentally different from another good Guji Gr-1, to give an example.

In Ethiopia, processing is where fundamental changes can happen in the quality of the coffee, but it hasn’t evolved much yet. So both traceability and the ability to re-buy coffee year-to-year is something that isn’t really possible in Ethiopia yet – but the ability to re-buy wouldn’t make much of a difference anyway until processing is revolutionized.

Ethiopia Guji beans

Melanie Leeson: So, so, so many more questions… We could write a book about how coffee works in Ethiopia. Thank you for shedding some light on these points. I look forward to learning more and seeing how the link between traceability and quality develops over time here.