Some of CCS’ strongest and longest standing partnerships were built in East Africa, and in Ethiopia specifically. Laws and trading parameters, restrictions and possibilities, they are changing all the time. As much as we want to hold onto things that work, we keep a dynamic approach and curious mind, always holding the door open for change and improvement.

A recent transparency reform at the ECX, plus an easing of restrictions on export licenses for coffee suppliers, has opened the market. While new opportunities are great, opportunism is not, so we were cautious when it came to meeting new partners taking advantage of these new trading arrangements.

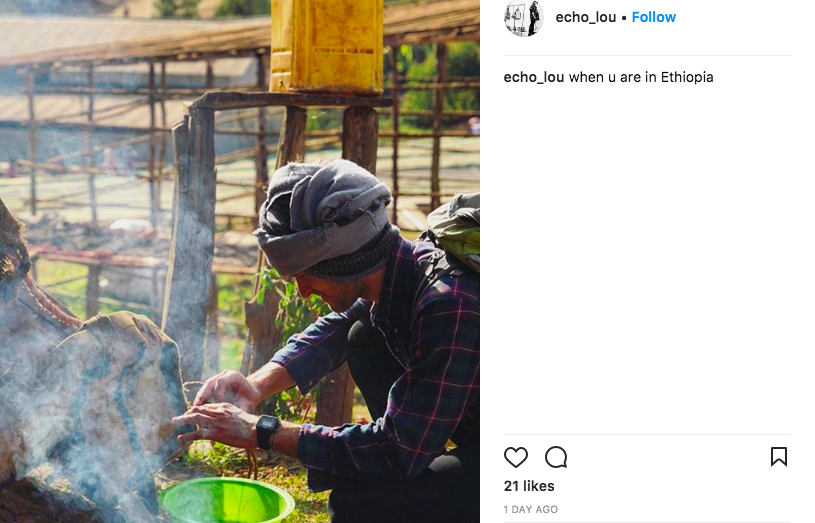

On the streets of Addis, beyond dusty air and traffic jams, behind construction sites, piles of gravel and hordes of goats, we were introduced to a mild mannered, helpful and service-oriented Abenezer Asfaw. Abenezer is the Supply Chain Manager for Snap, one of those new specialty coffee companies taking advantage of a more open market.

Abenezer Asfaw, Supply Chain Manager for Snap Specialty Coffee, our new partners in Ethiopia

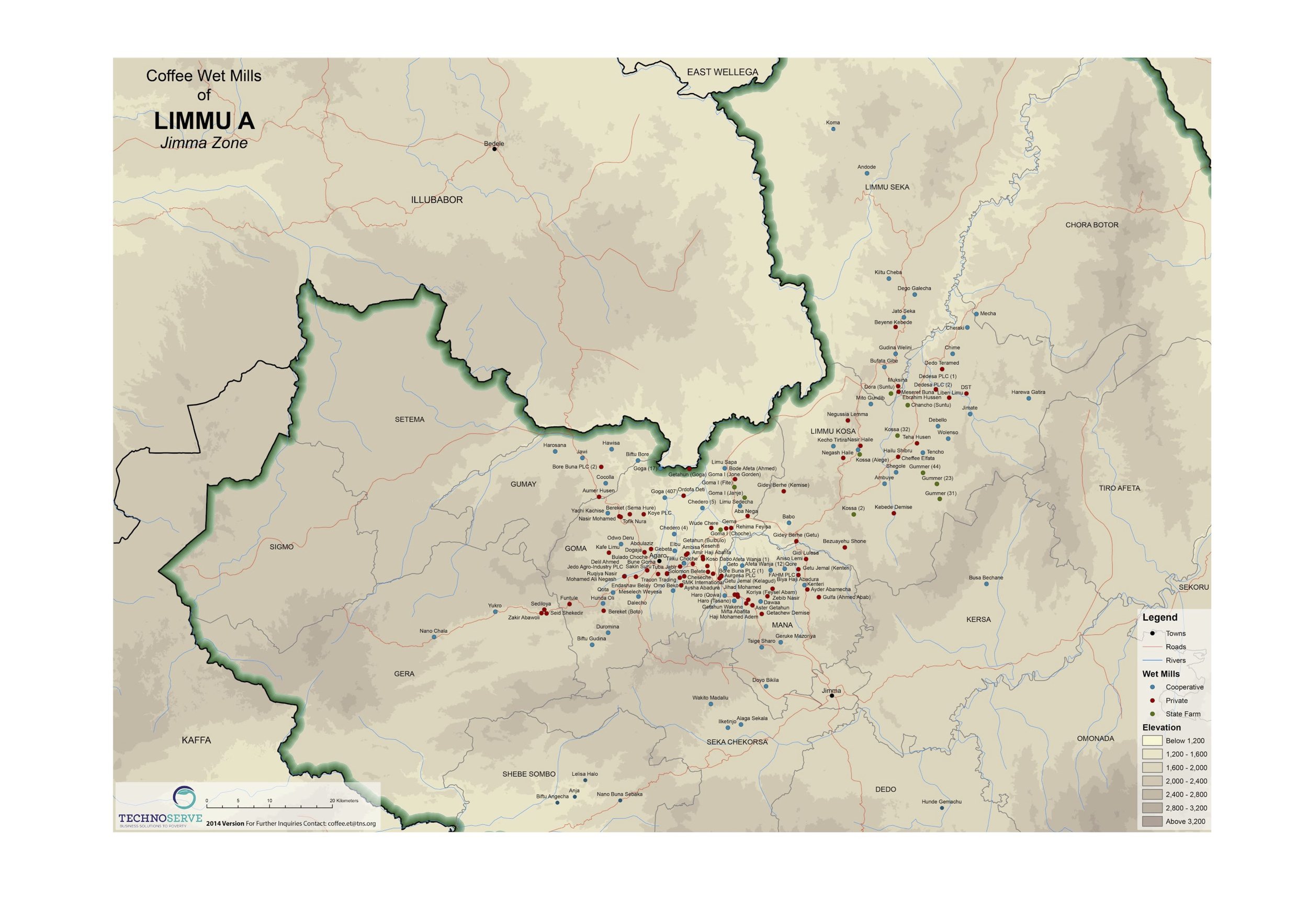

Snap was established by Negusse D. Weldyes, for whom Abenezer is the right and left hand. The company has its own washing stations in Guji, Gedeo and West Arsi, and it also manages coffees on behalf of other washing station owners such as Daniel Mijane in Gedeb, and the Jebril brothers in Uraga, to name a few. Their coffees are meticulously processed, washed and naturals alike. Starting next season, all coffees exported by Snap will be hulled and screened, sorted and bagged at their own dry milling facility in Addis.

It was clear from the outset that Snap is a company with a long-term commitment to producing well-crafted coffees, not out to make a quick buck before the export license system changes again. Controlling and following up on the last and final steps of the coffee’s journey out of Ethiopia is key, and Snap have proved they have the know-how and infrastructure to make that happen. That is why we have partnered with them.

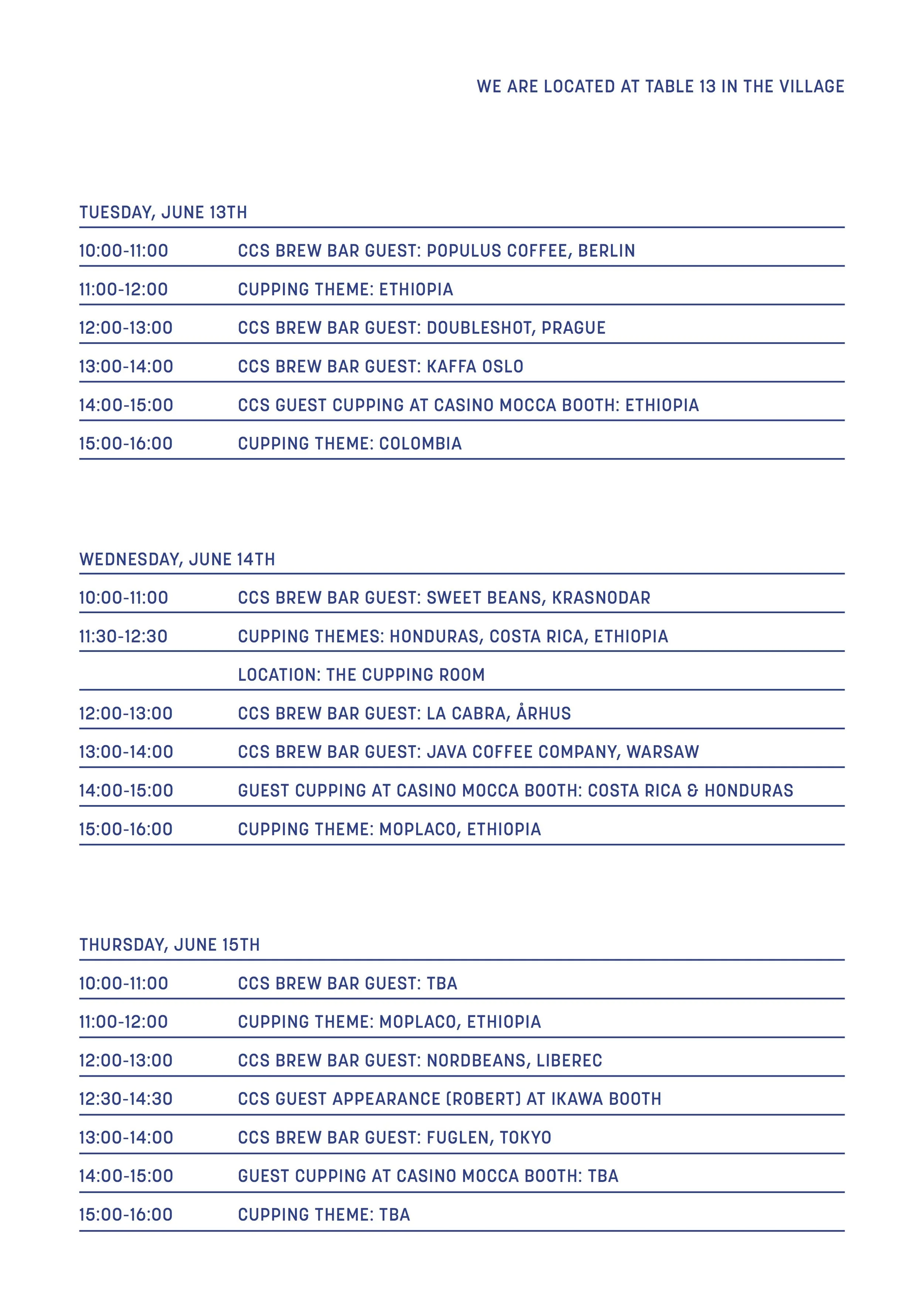

CCS PRESENCE IN ETHIOPIA, JAN AND FEB 2019

CCS will be working closely with Abenezer and his team, sharing cupping tables, lab functions and offices in the Snap building on Bole Road, Addis Ababa.

Robert will be in Addis from January 11th to the 28th. If you are passing through town, we invite you to the lab to cup with us.

Matt will be leading an official buying trip with customers for CCS from Feb 4th to Feb 11th, 2019. Email Matt to find out more.

If you will be visiting outside of these days, get in touch, we can arrange a cupping of CCS coffees with the team at Snap.

See you in Ethiopia!